1. Introduction

Transition is the term used to describe the process which is in place to support young people and their families move from services they have received as a child into those that they need when they become an adult.

Effective person centred transition planning is essential to help young people and their families prepare for adulthood. Transition to adult care and support comes at a time when a lot of change can take place in a young person’s life. It can also mean changes to the care and support they receive from education, health and care services, or involvement with new agencies such as those who provide support for housing, employment or further education and training.

The years in which a young person is approaching adulthood should be full of opportunity. Some of the issues that matter for young people approaching adulthood, and their families, may include (but are not limited to):

- paid employment;

- good health;

- completing exams or moving to further education;

- independent living (choice and control over one’s life and good housing options);

- social inclusion (friends, relationships and community).

The wellbeing of each young person or carer must be taken into account so that assessment and planning is based around the individual needs, wishes, and outcomes which matter to that person (see Promoting Wellbeing chapter).

Historically, there has sometimes been a lack of effective planning for people using children’s services who are approaching adulthood. Looked after children, young people with disabilities, and carers are often among the groups of people with the lowest life chances. Early conversations provide an opportunity for young people and their families to reflect on their strengths, needs and desired outcomes, and to plan ahead for how they will achieve their goals.

Professionals from different agencies, families, friends and the wider community should work together in a coordinated manner around each young person or carer to help raise their aspirations and achieve the outcomes that matter to them.

The purpose of carrying out transition assessments is to provide young people and their families with information so that they know what to expect in the future and can prepare for adulthood.

Transition assessments can develop solutions which do not necessarily involve the provision of services, and which may aid planning that helps to prevent, reduce or delay the development of needs for care or support.

2. When a Transition Assessment must be Carried Out

Transition assessments should take place at the right time for the young person or carer and at a point when the local authority can be reasonably confident about what the young person’s or carer’s needs for care or support will look like after the young person in question turns 18. There is no set age when young people reach this point; every young person and their family are different, and as such, transition assessments should take place when it is most appropriate for them.

The local authority must carry out a transition assessment of anyone in the three groups when there is significant benefit to the young person or carer in doing so, and if they are likely to have needs for care or support after turning 18. The provisions in the Care Act relating to transition to adult care and support are not only for those who are already receiving children’s services, but for anyone who is likely to have needs for adult care and support after turning 18.

3. Significant Benefit

When considering if it is of ‘significant benefit’ to assess, the local authority should consider the circumstances of the young person or carer, and whether it is an appropriate time for the young person or carer to undertake an assessment which helps them to prepare for adulthood.

The consideration of ‘significant benefit’ is not related to the level of a young person or carer’s needs, but rather to the timing of the transition assessment.

When considering whether it is of significant benefit to assess, a local authority should consider factors which may contribute to establishing the right time to assess (including but not limited to the following):

- the stage they have reached at school and any upcoming exams;

- whether the young person or carer wishes to enter further / higher education or training;

- whether the young person or carer wishes to get a job when they become a young adult;

- whether the young person is planning to move out of their parental home into their own accommodation;

- whether the young person will have care leaver status when they become 18;

- whether the carer of a young person wishes to remain in or return to employment when the young person leaves full time education;

- the time it may take to carry out an assessment;

- the time it may take to plan and put in place the adult care and support;

- any relevant family circumstances;

- any planned medical treatment/

For young people with special educational needs or disabilities (SEND) who have an education, health and care (EHC) plan under the Children and Families Act 2014, preparation for adulthood must begin from year 9 – see Special Educational Needs & Disability (SEND) Code of Practice. The transition assessment should be undertaken as part of one of the annual statutory reviews of the EHC plan, and should inform a plan for the transition from children’s to adult care and support.

Equally for those without EHC plans, early conversations with local authorities about preparation for adulthood are beneficial – when these conversations begin to take place will depend on individual circumstances.

For care leavers, local authorities should consider using the statutory Pathway Planning process as the opportunity to carry out a transition assessment where appropriate.

Local authorities should not carry out the transition assessment at inappropriate times in a young person’s life, such as when they are sitting their exams and it would cause disruption. The SEND Code of Practice similarly states that local authorities must minimise disruption to the child and their family – for example by combining multiple appointments where possible. Local authorities should seek to agree the best time for assessments and planning with the young person or carer, and where appropriate, their family and any other relevant partners.

In more complex cases, it can take some time not only to carry out the assessment itself but to plan and put in place care and support. Social workers will often be the most appropriate lead professionals for complex cases. Transition assessments should be carried out early enough to ensure that the right care and support is in place when the young person moves to adult care and support.

When transition assessments take place too late and care and support is arranged in a hurry, it can result in care and support which does not best meet the young person or carer’s needs – and sometimes at greater financial cost to the local authority than if it had been planned properly in advance.

4. Requests for Transition Assessment

A young person or carer, or someone acting on their behalf, has the right to request a transition assessment. The local authority must consider such requests and whether the likely need and significant benefit conditions apply – and if so it must undertake a transition assessment.

5. Refusal of Transition Assessment

If the local authority thinks these conditions do not apply and refuses an assessment on that basis, it must provide its reasons for this in writing in a timely manner, and it must provide information and advice on what can be done to prevent or delay the development of needs for support.

Where someone is refused (or they themselves refuse) a transition assessment, but at a later time makes a request for an assessment, the local authority must again consider whether the likely need and significant benefit conditions apply, and carry out an assessment if so.

6. Identifying Young People and Young Carers who are not already receiving Children’s Services

Most young people who receive transition assessments will be children in need under the Children Act 1989 and will already be known to local authorities.

However, local authorities should consider how they can identify young people who are not receiving children’s services who are likely to have care and support needs as an adult. Key examples include:

- young people with degenerative conditions;

- young people (for example with autism) whose needs have been largely met by their educational institution, but who once they leave, will require their needs to be met in some other way;

- young people detained in the youth justice system who will move to the adult custodial estate;

- young carers whose parents have needs below the local authority’s eligibility threshold but may nevertheless require advice or support to fulfil their potential, for example a child with deaf parents who is undertaking communication support;

- young people and young carers receiving Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) may also require care and support as adults even if they did not receive children’s services from the local authority.

Even if they are not eligible for services, a transition assessment with good information and advice about support in the community can be particularly helpful for these groups as they are less likely to be aware of this.

When young people who have not been in contact with children’s services present to the local authority as a young adult, they often do so with a high level of need for care and support. Local authorities should consider how to work with education and health services to identify these groups as early as possible so they can plan and prevent the development of care and support needs (see Integration, Cooperation and Partnerships and Special Educational Needs & Disability (SEND) Code of Practice ‘Preparing for Adulthood’).

7. Adult Carers and Young Carers

Preparation for adulthood will involve assessing how the needs of young people change as they approach adulthood and also how carers’, young carers’ and other family members’ needs might change over time.

The local authority must assess the needs of an adult carer where there is a likely need for support after the child turns 18 and it is of significant benefit to the carer to do so. For instance, some carers of disabled children are able to remain in employment with minimal support while the child has been in school. However, once the young person leaves education, it may be the case that the carer’s needs for support increase, and additional support and planning is required from the local authority to allow the carer to stay in employment.

The local authority must also assess the needs of young carers as they approach adulthood. For instance, many young carers feel that they cannot go to university or enter employment because of their caring responsibilities. Transition assessments and planning must consider how to support young carers to prepare for adulthood and how to raise and fulfil their aspirations.

The local authority must consider the impact on other members of the family (or other people the authority may feel appropriate) of the person receiving care and support. This will require the authority to identify anyone who may be part of the person’s wider network of care and support. For example, caring responsibilities could have an impact on siblings’ school work, or their aspirations to go to university. Young carers’ assessments should include an indication of how any care and support plan for the person/s they care for would change as a result of the young carer’s change in circumstances. For example, if a young carer has an opportunity to go to university away from home, the local authority should indicate how it would meet the eligible needs of any family members that were previously being met by the young carer.

8. Features of a Transition Assessment

The transition assessment should support the young person and their family to plan for the future, by providing them with information about what they can expect. All transition assessments must include an assessment of:

- current needs for care and support and how these impact on wellbeing;

- whether the child or carer is likely to have needs for care and support after the child in question becomes 18;

- if so, what those needs are likely to be, and which are likely to be eligible needs;

- the outcomes the young person or carer wishes to achieve in day to day life and how care and support (and other matters) can contribute to achieving them.

Transition assessments for young carers or adult carers must also specifically consider whether the carer:

- is able to care now and after the child in question turns 18;

- is willing to care now and will continue to after 18;

- works, or wishes to do so;

- is or wishes to participate in education, training or recreation.

The young person or carer in question must be involved in the assessment for it to be person centred and reflect their views and wishes. The assessment must also involve anyone else who the young person or carer wants to involve in the assessment. For example, many young people will want their parents involved in their process.

9. Capacity

See also Mental Capacity chapter

In all cases, the young person or carer in question must agree to the assessment where they have mental capacity and are competent to agree. Where a young person or carer lacks mental capacity or is not competent to agree, the local authority must be satisfied that an assessment is in their best interests. Everyone has the right to refuse a transition assessment, however the local authority must undertake an assessment regardless if it suspects that a child is experiencing or at risk of abuse or neglect.

The right of young people to make decisions is subject to their capacity to do so as set out in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The underlying principle of the Act is to ensure that those who lack capacity are supported to make as many decisions for themselves as possible, and that any decision made or action taken on their behalf, is done so in their best interests. This is a necessity if the transition assessment is to be person centred.

For young people below the age of 16, local authorities will need to establish a young person’s competence using the test of ‘Gillick competence’ (whether they are able to understand a proposed treatment or procedure). Where the young person is not competent, a person with parental responsibility will need to be involved in their transition assessment, – or an independent advocate provided if there is no one appropriate to act on their behalf (either with or without parental responsibility).

10. Independent Advocacy

The Care Act places a duty on local authorities to provide an independent advocate to facilitate the involvement in the transition assessment where the person in question would experience substantial difficulty in understanding the necessary information or in communicating their views, wishes and feelings – and if there is nobody else appropriate to act on their behalf (see Independent Advocacy chapter). This duty applies for all young people or carers who meet the criteria, regardless of whether they lack mental capacity as defined under the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

11. Information Sharing

When sharing information with a young carer about the person they care for a supported self-assessment during transition, the local authority must be satisfied that it is appropriate for the young carer to have the information. They must have regard to all circumstances in taking this decision, especially the age of the young carer, however each case will be different and there is no one age at which a young carer is necessarily old enough to receive information. The local authority must ensure that the adult consents to have their information shared in this way.

12. Cooperation between Professionals and Organisations

People with complex needs for care and support may have several professionals involved in their lives, and numerous assessments from multiple organisations. For children with special educational needs, the Children and Families Act 2014 brings these assessments together into a coordinated EHC plan (see SEND Code of Practice, Chapter 9).

Local authorities must cooperate with relevant partners, and this duty is reciprocal (see Integration, Cooperation and Partnerships chapter). This includes an explicit requirement which states that children and adult services must cooperate for the purposes of transition to adult care and support. Often, staff working in children’s services will have built relationships and knowledge about the young person or carer in question over a number of years. As young people and carers prepare for adulthood, children’s services and adults’ services should work together to pass on this knowledge and build new relationships in advance of transition.

It can be frustrating for children and families who have to attend multiple appointments for assessments, and who have to give out the same information repeatedly. The SEND Code of Practice highlights the importance of the ‘tell us once’ approach to gathering information for assessments and this will be important in other contexts as well. The local authority should consult with the young person and their family to discuss what arrangements they would prefer for assessments and reviews.

All relevant partners should be involved in transition planning where they are involved in the person’s care and support.

Equally, the local authority should be involved in transition planning led by another organisation, for example a child and adolescent mental health service, where there are also likely to be needs for adult care and support.

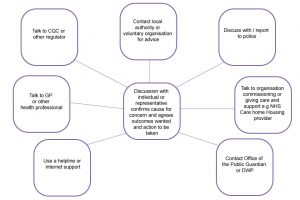

Agencies should agree how to organise transition assessments so that all the relevant professionals are able to contribute. For example, this might involve arranging a multi-disciplinary team meeting with the young person or carer. However, it may not always be possible for all the professionals from different agencies to be present at appointments, but they should still be enabled to contribute. Transition assessments must be person centred, which means that contributions by different agencies should reflect the views of the person to whom the assessment relates.

12.1 Care coordination

Many people value having one designated person who coordinates assessments and transition planning across different agencies, and helps them to navigate through numerous systems and processes that can sometimes be complicated.

Often there is a natural lead professional involved in a young person’s care who fulfils this role and the local authority should consider formalising this by designating a named person to coordinate transition assessment and planning across different agencies, and may also wish to consider setting up specialist posts carry out this coordination function for people who are preparing for adulthood.

This coordinating role, sometimes referred to as a ‘key working’ or ‘care coordination’, can not only help to deliver person centred, integrated care, but can also help to reduce bureaucracy and duplication for local authorities, the NHS and other agencies. Care coordinators are also often able to build close relationships with young people and families and can act as a valuable provider of information and advice both to the families and to local authorities. Care leavers will have Personal Advisers to provide support, for example by providing advice or signposting the young person to services. The Personal Adviser will be a natural lead in many cases to coordinate a transition from children’s to adult care and support where relevant (see also Transitions Case Studies).

13. Eligibility

Having carried out a transition assessment, the local authority must give an indication of which needs are likely to be eligible needs (and which are not likely to be eligible) once the young person in question turns 18, to ensure that the young person or carer understands the care and support they are likely to receive and can plan accordingly.

There is a particularly important role for local authorities in ensuring that young people and carers understand their likely situation when they reach adulthood. The different systems for children’s and adult care and support mean that there will be circumstances in which needs that were being met by children’s services may not be eligible needs under the adult system.

Adult care and support is subject to means testing and charging.

Where the transition assessment identifies needs that are likely to be eligible, local authorities should consider providing an indicative personal budget, so that young people, carers and their families are able to plan their care and support before entering the adult system (see SEN code of practice for further information about right to a personal budget for people with EHC plans).

For any needs that are not eligible under the adult statute, local authorities must provide information and advice on how those needs can be met, and how they can be prevented from getting worse.

14. Transition Plans

The local authority and relevant partners should consider building on a transition assessment to create a person-centred transition plan that sets out the information in the assessment, along with a plan for the transition to adult care and support, including key milestones for achieving the young person or carer’s desired outcomes.

In the case of an adult carer, if the local authority has identified needs through a transition assessment which could be met by adult services, it may meet these needs under the Care Act in advance of the child being cared for turning 18.

In deciding whether to do this the local authority must have regard to what support the adult carer is receiving under children’s legislation.

If the local authority decides to meet the adult carer’s needs through adult services, as for anyone else under the adult legislation, the adult carer must receive a support plan and a personal budget – as well as a financial assessment if they are subject to charges for the support they will receive.

15. Moving to Adult Care after the Young Person or Carer turns 18

There is no obligation on the local authority to move from children’s social care to adult care and support as soon as someone turns 18.

Very few moves will take place on the day of someone’s 18th birthday.

For the most part, the move to adult services begins at the end of a school term or another similar milestone, and in many cases should be a staged process over several months or years.

Prior to the move taking place, the local authority must decide whether to treat the transition assessment as a needs or carers assessment under the Care Act.

In making this decision the local authority must take into account when the transition assessment was carried out and whether the person’s circumstances have changed.

If the local authority will meet the young person’s or carer’s needs under the Care Act after they have turned 18 (based either on the existing transition assessment or a new needs assessment if necessary), the local authority must then undertake the care planning process as for other adults – including creating a care and support plan and producing a personal budget.

The local authority should ensure that this happens early enough that a package of care and support is in place at the time of transition.

16. Continuity of Care after the age of 18

Young people and their carers have sometimes faced a gap in provision of care and support when they turn 18, and this can be distressing and disruptive to their lives.

The local authority must not allow a gap in care and support when young people and carers move from children’s to adult services.

If transition assessment and planning is carried out as it should be, there should not be any gap in provision of care and support.

However, if adult care and support is not in place on a young person’s 18th birthday, and they or their carer have been receiving services under children’s legislation, the local authority must continue providing services until the relevant steps have been taken, so that there is no gap in provision.

The ‘relevant steps’ are if the local authority:

- concludes that the person does not have needs for adult care and support;

- concludes that the person does have such needs and begins to meet some or all of them (the local authority will not always meet all of a person’s needs – certain needs are sometimes met by carers or other organisations);

- concludes that the person does have such needs but decides they are not going to meet any of those needs, for instance, because their needs do not meet the eligibility criteria under the Care Act 2014.

In order to reach such a conclusion, the local authority must have conducted a transition assessment (that they will use as a needs or carers assessment under the adult statute).

Where a transition assessment was not conducted and should have been (or where the young person’s circumstances have changed), the local authority must carry out an adult needs or carer’s assessment.

In the case of care leavers, the Staying Put Guidance (HM Government, 2013) states that local authorities may choose to extend foster placements beyond the age of 18. All local authorities must have a Staying Put policy to ensure transition from care to independence and adulthood that is similar for care leavers to that which most young people experience, and is based on need and not on age alone.

For some people with complex SEN and care needs, local authorities and their partners may decide that children’s services are the best way to meet a person’s needs – even after they have turned 18. Both the Care Act 2014 and the Children and Families Act 2014 allow for this.

The Children and Families Act enables local authorities to continue children’s services beyond age 18 and up to 25 for young people with EHC plans if they need longer to complete or consolidate their education and training and achieve the outcomes set out in their plan.

Under the Care Act 2014, if, having carried out a transition assessment, it is agreed that the best decision for the young person is to continue to receive children’s services, the local authority may choose to do so.

Children and adults’ services must work together, and any decision to continue children’s services after the child turns 18 will require agreement between children and adult services.

Where a person over 18 is still receiving services under children’s legislation through their EHC plan and the EHC plan ceases, the transition assessment and planning process must be undertaken. Where this has not happened at the point of transition, the requirement under the Care Act to continue children’s services (as set out above) applies.

Both the Children and Families Act 2014 and the Care Act 2014 also require young people and their parents to be fully involved making decisions about their care and support. This includes decisions about the most appropriate time to make the transition to adult services.

The EHC plan or any transition plan should set out how this will happen, who is involved and what support will be provided to make sure the transition is as seamless as possible.

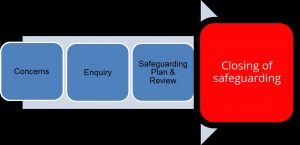

17. Safeguarding after the age 18

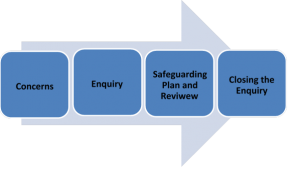

Where someone is over 18 but still receiving children’s services and a safeguarding issue is raised, the matter should be dealt with by the adult safeguarding team (see Safeguarding Enquiries Process).

Where appropriate, they should involve the local authority’s children’s safeguarding colleagues as well as any relevant partners (for example police or NHS) or other persons relevant to the case.

The same approach should apply for complaints or appeals, as well as where someone is moving to a different local authority area after receiving a transition assessment but before moving to adult care and support.

18. Transition from Children’s to Adult NHS Continuing Health Care

ICBs should use the National Framework for NHS Continuing Healthcare and supporting guidance and tools (especially the Decision Support Tool) to determine what ongoing care services people aged 18 years or over should receive.

The framework sets out that ICBs should ensure that adult NHS continuing healthcare is assessed at all transition planning meetings for all young people whose may be potential eligibility.

ICBs and LAs should have systems in place to ensure that appropriate referrals are made whenever either organisation is supporting a young person who, on reaching adulthood, may have a need for services from the other agency.

The framework sets out best practice for the timing of transition steps as follows:

- children’s services should identify young people with likely needs for NHS Continuing Health Care and notify the relevant ICB when such a young person turns 14;

- there should be a formal referral for adult NHS CHC screening at 16;

- there should be a decision in principle at 17 so that a package of care can be in place once the person turns 18 (or later if agreed more appropriate).

Where a young person has been receiving children’s continuing health care, it is likely that they will continue to be eligible for a package of adult NHS CHC when they reach the age of 18.

Where their needs have changed such that they are assessed as no longer requiring such a package, they should be advised of this and of their right to request an independent review and mediation

The ICB should continue to participate in the transition process, in order to ensure an appropriate transfer of responsibilities, including consideration of whether they should be commissioning, funding or providing services towards a joint package of care.

Where it will benefit a young person with an EHC plan, local authorities have the power to continue to provide children’s services past a young person’s 18th birthday for as long as is deemed necessary.

Where there is a change in CHC provision, this must be recorded in the young person’s EHC plan, where they have one, and the young person must be advised of their right to ask the local authority for mediation up to the age of 25 (see SEND Code of Practice).

Thanks for your feedback!